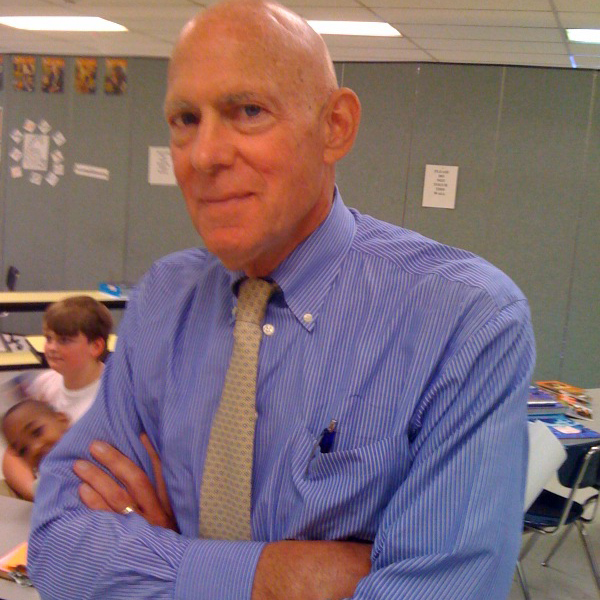

About The Founder

Tom McJunkin’s Legacy: Paying It Forward for West Virginia Students

Humans react to adversity in many ways. Some retreat and give up. Some fight back against unbeatable odds. A wise and generous few, like Tom McJunkin, cast a lifeline into the future for others. Ten years after his death, his gifts to children keep on giving.

Humans react to adversity in many ways. Some retreat and give up. Some fight back against unbeatable odds. A wise and generous few, like Tom McJunkin, cast a lifeline into the future for others. Ten years after his death, his gifts to children keep on giving.

In 2007, in his capacity as a partner in the law firm of Jackson Kelly, Tom had volunteered for over 20 years at Charleston’s Piedmont Elementary School, reading to children through Read Aloud. He enjoyed it, and so did the children, but he sensed that some needed more than an enjoyable group experience.

Steve Knighton, then the principal at Piedmont Elementary, remembers what came next: “Tom realized that we could do some other things that would be more beneficial than just reading to kids. He convinced his managing partners to volunteer the time for people to do a one-on-one mentorship with these kids.”

McJunkin chose the name Education Elevators for the new program, and that’s just what the mentors did, according to Knighton: “You take a single child and, even though they’re struggling, give them encouragement, build on their successes. You lift them up.

“Many of our kids did not have a supportive family unit. It may have been for legitimate reasons: Mom was working two jobs, there was a grandmother raising two kids, whatever. They lacked someone to reinforce the positives in their lives.

“These kids, they just soaked up this stuff. And they became the stars in the classroom! Maybe not academically, but anybody who did not have an Elevator was jealous. “Tom shepherded this thing through its infancy.

Tom walked the walk. It wasn’t just words. He would come to our meetings. He would throw out suggestions that we didn’t even imagine possible.”

And he recruited others. Before long, dozens of Jackson Kelly’s partners and employees were mentoring students at Piedmont. Knighton recalls, “Success breeds success, and Tom’s mission was to get as many mentors into the school system as possible. It grew and grew. We would hold a luncheon, and there would be fifty mentors in the school. It just blossomed.

“Tom was the virtuoso behind this. He orchestrated this entire meaningful event. Even when he was struggling [with cancer], he never failed to show up.”

Taking It to the Next Level

Education Elevators has continued to grow. Since then, his pilot program has grown to include partnerships between ten West Virginia businesses and nine schools and afterschool programs. McJunkin’s daughter Allison McJunkin, who in 2011 left a law career to direct the organization’s work, is a tireless promoter of her father’s legacy.

“I am so passionate about Education Elevators because I have seen the impact of a strong mentoring relationship. It’s almost magical.” She says. “My dad was my Elevator, and I am on a mission to carry on his vision, his love for education, and his legacy. “When I was contemplating attending law school in 2000, my dad sent me a letter saying ‘I think that law school is a good choice for you. Not that you shouldn't consider other options. But a law degree, together with your experience, charm, and ability to organize and motivate people, will give you many options, including management of a nonprofit organization.’ “I graduated with my J.D. from Washington & Lee in 2004, but somehow he knew where my path following law school would eventually lead me. Nonprofit management was never something I considered until Education Elevators fell into my lap. But it seems like all of my life experiences were meant to lead me exactly where I am.”

Why Educators Love Elevators

Mentoring a child, especially an elementary student, is an investment in the future, and progress is not easily gauged in the short term. Still, there are immediate benefits—and not just for students.

Becca Revercomb, who taught fifth grade at Piedmont before her retirement, explains: “I regarded the Education Elevators as colleagues. When you have a mentor and a teacher working together, that’s a good duo. And I think the Elevators, when they meet with a child, have been able to do things teachers are just unable to do. Teachers are hamstrung, they have too many things to do. For instance, cursive writing is no longer widely taught, and there’s research that connects cursive to brain development. And so many other things: playing games, writing poems and stories, doing crafts.

“I saw positive effects on the children: attention to detail, better attendance. They wanted to come to school more, especially on the days when their Elevator was coming.”

It Takes a Village

Natalie Blevins wears a lot of hats. She’s the after-school director and family support worker at Mary C. Snow and Grandview Elementary Schools and also a coordinator and family liaison for Education Elevators. Among many other duties, she matches up mentors with at-risk children.

“I think the match is very important—for the student, the family, and the Elevator,” says Blevins. She follows their progress, champions their successes, and sometimes goes the extra mile—literally—to facilitate their get-togethers. She related the story of one student’s experience with his Elevator.

“One particular boy—he was a 5th-grade boy—struggled academically, socially, emotionally. He was never picked for games, he didn’t have friends. After school, he would play with kindergartners if he could. That’s where he felt comfortable.

“This little boy loved Legos and trains, so I told his Elevator. His Elevator would come twice a week, and if the student really tried, then they would build a section of the train. His resource teacher approached me and said, ‘What are you doing? What’s going on with him?’ Because he was actually beginning to pass tests. His attendance improved for the first time since he began coming to school. He was turning in work, he was writing out answers.

“I saw him smile, I saw him talk more, he would look up when he walked, and he started interacting with his peers. One day he told me, ‘It’s going to be the best day of my life.’ It was his birthday, the school dance, and his Elevator was coming.

His Elevator is committed to following him all the way through his high school years. If he can get a high school diploma, he will be the first one in his family.

“I had another little boy who absolutely adored the attention. He would tell anyone who would listen. He kept talking and talking. So his teacher called him to the front of the class and said, ‘Okay, you’re just going to tell us what’s so important.’ So he gave this three-minute presentation about his Elevator. My telephone started blowing up. He single-handedly sold the program! Everyone was asking me, ‘Please, please match me up with an Elevator.’”

An Elevator’s Incentives

Elevators volunteer for many reasons. Chris May, an information security consultant at Advantage Technology, has several.

Having experienced broken family ties and economic hardship during his own childhood, he can relate to kids who are struggling. And he wants to pass along some of what he learned.

“I was lucky,” he says. “I had some people who cared about me. Both of my grandfathers listened to me and really helped me.” He credits them with steering him away from “some bad paths I was taking.

“I don’t have children of my own. Instead, I see these kids who don’t have a parent or a mentor or a hero or a role model in their life. I have the time and I have the energy.

“When I met [my mentee], at about eight years old, it was just anger, confusion. He had a massive desire to learn, but he didn’t know where to look for direction. I know how sad he can get, and how angry, but every time I see him, he smiles. It just lights me up. I see something good in him.

“These kids begin to trust us. They begin to tell us about things. That’s what it does for me to see him, just to give him thirty minutes of healing.”

May says there are benefits to his company, too: “I believe it does help the company. We’re in a world right now where a lot of people are very insulated and believe they know the truth about what’s going on. The more we can get people involved with the real world, outside of what they see at home and on their news channels and their Facebook feed, the more they’re going to start to understand what real problems there are in this world. They begin to understand that there are children out there who are struggling, that don’t have the resources their own kids do. They become better people—and that’s somebody in our company, now, that has a better mindset.”

A Lasting Impact

Tom McJunkin’s influence—even ten years after his death—continues to improve the lives and enrich the futures of young people. Shaunn Monroe, a college freshman at the University of Charleston , who was mentored by McJunkin more than a decade ago, shares some thoughts about his experience. “What I remember most about Mr. McJunkin was how kind he was and how much he genuinely cared,” Shaunn says. “Having him as my Elevator made me feel good. I feel like he made an impact on my life at a young age and kept me on the right track.

“During our time together we played games and read a lot of books. We talked about each other’s day, life, and the books we read.

“We practiced giving a firm handshake and making eye contact. He said that it was very important in life. I think about this all the time, meeting new people, now, and I make sure that I do it every time in his honor.”

Education Elevators is a West Virginia based, non-profit organization that partners businesses and organizations with local schools to match their employees with students in need of mentors, role models, friendship, academic support, and individual attention.By impacting individual students, we respond to fundamental needs in our communities.Education Elevators is designed to facilitate and support meaningful mentoring partnerships of businesses and organizations with local elementary schools.

Subscribe to receive EE updates and our newsletter!